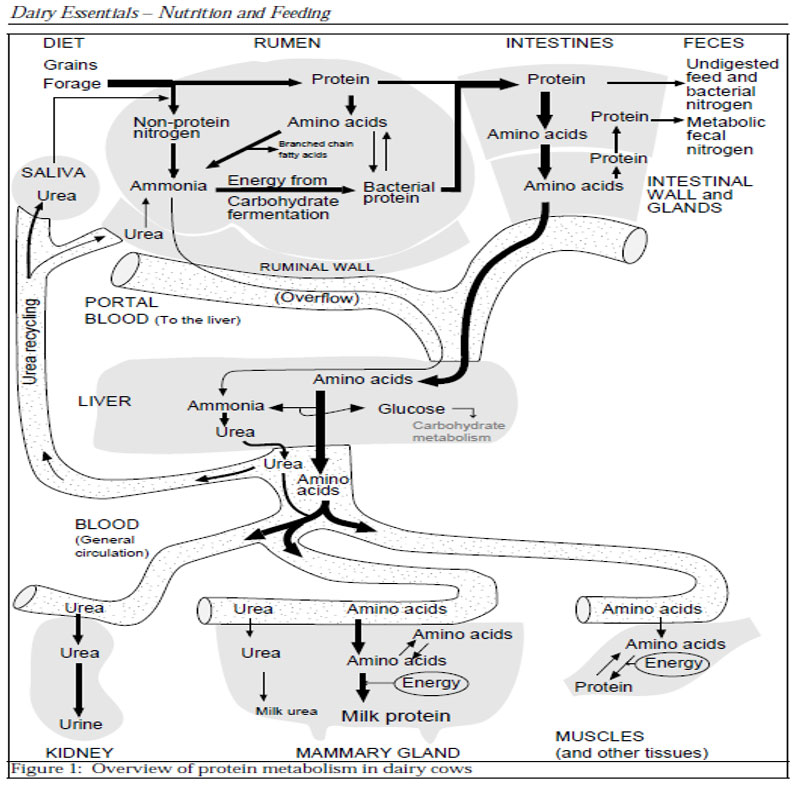

Il Metabolismo dell’azoto nelle vacche da latte:

(by M. Wattiaux – Babcock Institute for International Dairy Research and Development University of Wisconsin – 2014)

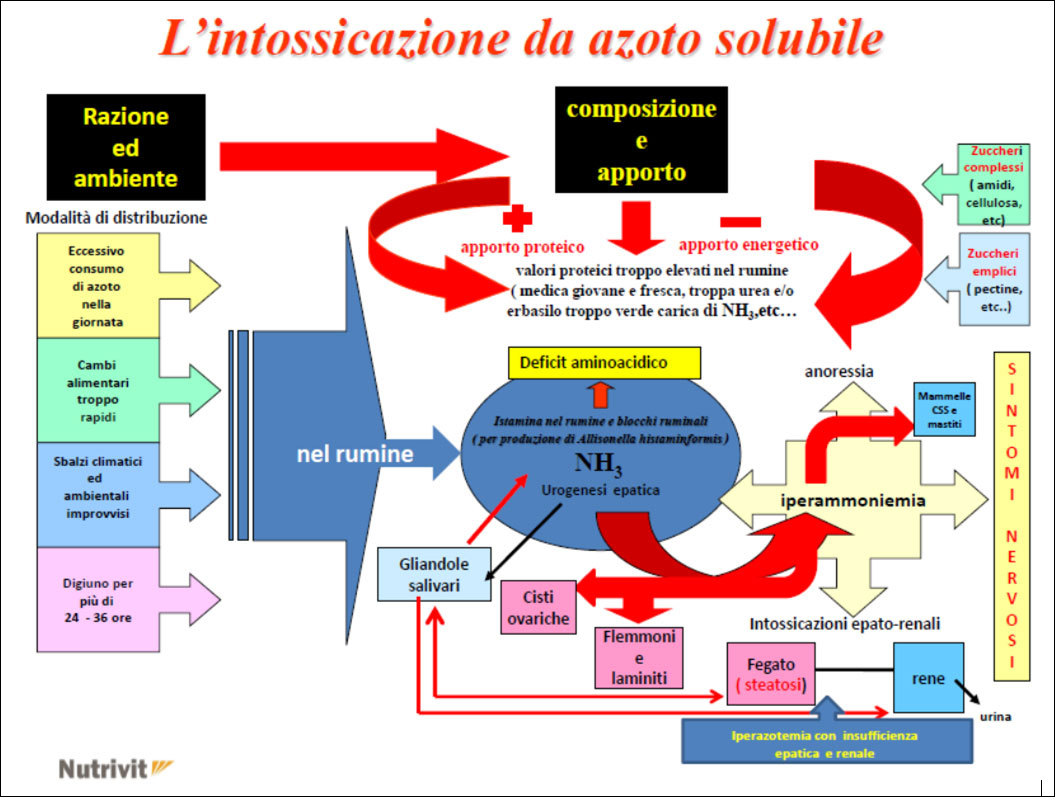

Aumento dell’azoto ammoniacale nel rumine:

Il cambio del pH ruminale provocato da un repentino e/o forte aumento dell’azoto solubile nel rumine ( squilibrio proteico), conseguente a:

- una eccessiva ingestione di foraggio proteico fresco altamente solubile ( es: eccessive dosi di pascolo verde ricco di azoto solubile come erba medica e/o trifoglio,etc…)

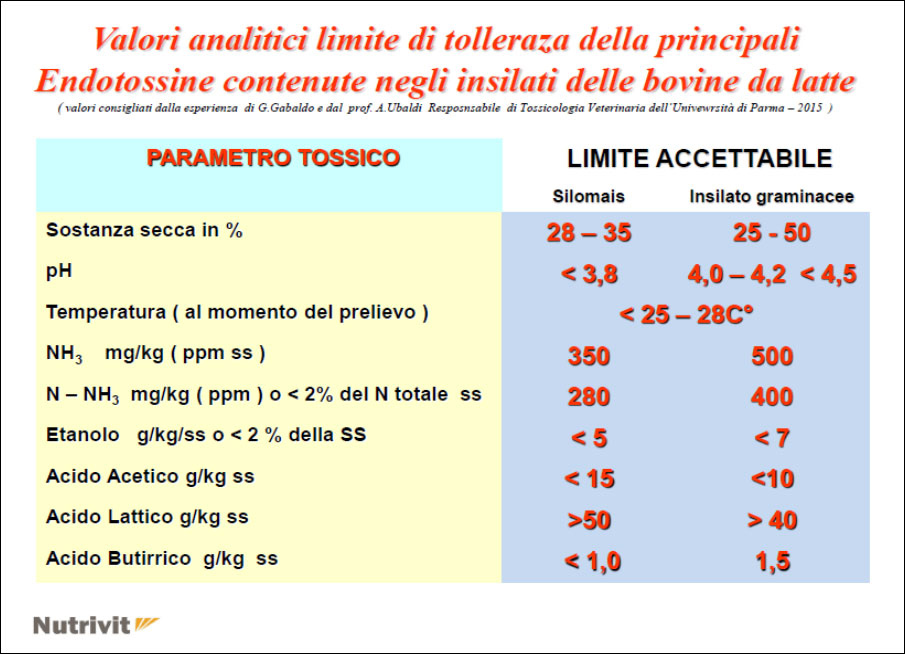

- l’impiego di dosi elevate di insilati con un alto contenuto di amoniaca NH3 in forma libera nella razione, etc… provoca sia una intossicazione da azoto solubile nel rumine a cui può seguire anche una alcalosi acuta ( solo su qualche soggetto ) come un aumento di azoto ammoniacale a livello ruminale e metabolico (forma sub-acuta), che poi, in pratica, è anche la più dannasa ai fini economici in quanto colpisce tutta la mandria.

Ricadute sulla salute e produzioni degli animali:

Tale situazione a livello ruminale crea le condizioni ideali per lo sviluppo della Allisonella histaminiformans, microorganismo ubiquitario del rumine produttore di istamina che ha come conseguenza:

- l’immediata infiammazione delle papille ruminali ( per aumento delle citochine circolanti ) e conseguente riduzione dell’assimilazione degli AGV ( Acidi Grassi Volatili ) a cui segue l’attivarsi di patologie a carico di:

- mammella ( aumento dello stato infimmatorio nella mammella e di conseguenza più CSS e mastiti )

- piedi ( formazione di trombi a livello amatico >> flemmoni interdigitali >> laminiti )

- ovaie ( cisti ovariche )

- in qualche animale può manifestarsi anche la forma acuta ( alcalosi acuta ) con patologie a carico di:

- fegato (steatosi epatica)

- dei reni (nefriti)

e nelle forme gravi - SNC ( sintomi neuroplegici con atassia, alterata deambulazione etc…ed in alcuni casi coma e morte del soggetto colpito)

Interventi da fare sulla razione per le forme sub-acute per migliorare la salute, la riproduzione e la produzione delle bovine:

- Eliminazione e/o riduzione della fonte alimentare tossica di azoto ( erbasilo, erba verde, urea, etc… ) ed aggiungere alla razione il mix sottoindicato

- Mix di sodio propionato 100 g/capo/gg + di Micronil ® (ProbioactiFAP® ) 20 g. capo/gg + ANTIGRIP FEED ( fitoterapico NUTRIVIT-COFATHIM) ad azione antinfimmatoria alla dose di 50g. capo/gg) , tale mix deve essere somministrato fino al termine dell’utilizzo nella dieta della fonte alimentare “ tossica” e continuare per almeno altri 10 giorni.

RIFERIMEMENTI BIBLIOGRAFICI

– Anon. Third External Review Draft of Air Quality Criteria for Particulate Matter (April, 2002). Volume I, II. EPA. United States Department of Environmental Protection Agency. www.epa

– Bach A., Calsamiglia, S. and Stern, M.D. 2005. Nitrogen Metabolism in the Rumen J. Dairy Sci., 88: 9 – 21 Baker, L.D., J.D. Ferguson, and C.F. Ramberg. Kinetic analysis for urea transport from plasma to milk in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 75 (Supplement 1):181, 1992.

– Baker, JL, 2001. Limitations of improved nitrogen management to reduced nitrate leaching and increase use efficiency. Optimizing Nitrogen Management in Food andEnergy Production and Environmental Protection: Proceedings of the 2 nd International Nitrogen Conference on Science and Policy. The Scientific World 1(S2), 1016.

– Cowling, E., J. Galloway, C. Furiness, M. Barber, T. Bresser, K. Cassman, J.W. Erisman, R.Haeuber, B. Howarth, J. Melillo, W. Moomaw, A. Mosier, K. Sanders, S. Seitzinger, S.Smeulders, R. Socolow, D. Walters, F. West, and Z. Zhu. 2001. Optimizing nitrogen management in food and energy production and environmental protection: Summary Statement from the Second International Nitrogen Conference. TheScientificWorld 1(S2): 19. DePeters, E.J. and J.D. Ferguson. 1992. Nonprotein nitrogen and protein distribution in the milk of cows. J. Dairy Sci. 75:31923209.

– Dou, Z., D.T. Galligan, C.F. Ramberg, Jr., C. Meadows, and J.D. Ferguson. 2001. A survey of dairy farming in Pennsylvania: Nutrient management practices and implications. J. Dairy Sci. 84:966973.

– Ferguson, J.D., Z. Dou, and C.F. Ramberg, Jr. 2001. An assessment of ammonia emissions from dairy facilities in Pennsylvania. TheScientificWorld 1(S2): 348355. Erickson, G.E. and T.J. Klopfenstein. 2001. Nutritional methods to decrease N losses from opendirt feedlots in Nebraska. TheScientificWorld 1(S2): 836843.

– Ganong, W.F. Review of Medical Physiology. Nineteenth edition . Co 1999. Appleton and Lange a Simon & Schuster Company. Stamford, Ct. 069120041.

– Hof, G., M.D. Vervoorn, P.L. Lenaers, and S. Tamminga. 1997. Milk urea nitrogen as a tool to monitor the protein nutrition of dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 80:33333340.

– Huhtanen, P. 1998. Supply of nutrients and productive responses in dairy cows given diets based on restrictively fermented silage. Agric. Food Sci. Finl. 7:219–250

– Jarvis, S.C., D.J. Hatch and D.H. Roberts. 1989a. The effects of grassland management on nitrogen losses from grazed swards through ammonia volatilization; the relationship to excretal N returns from cattle. J. agric. Sci. Camb. 112:205216.

– Jarvis, S.C., D.J. Hatch and D.R. Lockyer. 1989b. Ammonia fluxes from grazed grassland: annual losses from cattle production systems and their relation to nitrogen inputs. J. agric. Sci. Camb.113:99108.

– Jonker, J.S., R.A. Kohn, and R.A. Erdman. 1998. Using milk urea nitrogen to predict nitrogen excretion and utilization efficiency in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 81:26812692.Muck, R.E. and B.K. Richards. 1983. Losses of manurial N in freestall barns. Agric. Wastes 7:6579.

– Muck, R.E. 1982. Urease activity in bovine feces. J. Dairy Sci. 65:21572163.

– Muck, R.E. and F.G. Herndon. 1985. Hydrated lime to reduce manorial nitrogen losses in dairy barns. Transactions of ASAE 28:201208.

– NRC. 2001. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle. Seventh Revised Edition. National Academy Press. Washington D.C. NRC. 1996. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle. Seventh Revised Edition. National AcademyPress. Washington D.C.

– Roseler, D.K., J.D. Ferguson, C.J. Sniffen and J. Herrema. 1993. Dietary protein degradability effects on plasma and milk urea nitrogen and milk nonprotein nitrogen in Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 76:525534.

– Scholefield, D., D.R. Lockyer, D.C. Whitehead, and K.C. Tyson. 1991. A model to predict transformations and losses of nitrogen in UK pastures grazed by beef cattle. Plant and Soil132:165171.

– Smits, M.C.J., H. Valk, A. Elzing, and A. Keen. 1995. Effect of protein nutrition on ammonia emission from a cubicle house for dairy cattle. Live. Prod. Sci. 44:147156.

– Voorburg, J.H. and W. Kroodsman. 1992. Volatile emissions of housing systems for cattle.Livestock Prod. Sci. 31:5770.

– Wattiaux , M.A – Protein Metabolism in Dairy Cows – Babcock Institute for International Dairy Research and Development – University of Wisconsin-Madison -2014

– Wilkerson, V.A., D.R. Mertens, and D.P. Casper. 1997. Prediction of excretion of manure and nitrogen by Holstein dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 80:31933204.

– Van Horn HH. 1991;Managing Dairy Manure Resources to aviod Environmental pollution. J Dairy Sci 77:2008-1994.

– Van Horn HH. Balancing nutrients, manure use reduces pollution. Feedstuffs. The Miller Publishing Co. 1992; 64(Oct. 26, 1992). 11-23. Minnetonka, MN.

– Vanfaassen HG, Lebbink G. 1994;Organic matter and nitrogen dynamics in conventional versus integrated arable farming. Agr Ecosyst Environ 51:209-26.

– Vanhorn HH, Wilkie AC, Powers WJ, Nordstedt RA. 1994;Components of Dairy Manure Management Systems. J Dairy Sci 77:2008-30. Webb J, Archer JR. ; Dewi IA, Axford RFE, Marai IFM, Omed H, editors.Pollution in Livestock Production Systems. Oxon, UK: CAB International, 1994; 11,

– Pollution of Soils and Watercourses by Wastes from Livestock Production Systems. p. 189-204.

– Young CE, Crowder BM, Shortle JS, Alwang JR. 1985;Nutrient Management on Dairy Farms in Southestern Pennsylvania. J Soil Water Conserv 40:443-445.